To Address AI Risks, Draw Lessons From Climate Change

We can't solve the problem today; we *can* start establishing the conditions for it to be solved.

In A Unified Theory of AI Risk, I reviewed the long list of problems that advanced AI might pose, from turbocharged spam to human extinction. Today, I’ll talk about how we can rise to the occasion of mitigating these risks.

The key point is that we need to play a long game. However urgent the dangers may seem, we’ll be dealing with them for years to come, and panic is not a good strategy. The grand project of mitigating climate change offers some useful lessons: to enact serious change, we must create organizations that can craft effective strategies and messages, and patiently build relationships between those organizations and people in positions of power. As technical solutions emerge, those organizations and relationships will allow us to put the solutions into practice.

All of this will need to be underpinned by a gradual shift in public opinion, normalizing the idea that AI is a technology requiring regulation. Positive messages (not doomerism), crafted for a general audience, are the best way to drive that shift. Early victories, even if they don’t meaningfully address the big risks, will create momentum for further action.

AI Risk Can Seem Overwhelming

Some people have been concerned about AI risks for years, and have become dispirited by the historic lack of engagement. They see OpenAI, Google, and others racing forward, and despair of coming to our collective senses in time to avoid disaster.

Others were not paying much attention to AI, and were caught off guard by the sudden prominence of tools like Midjourney and ChatGPT. For them, it can seem as if human-level AI will be here any day now, before we have any idea how to handle it. Simultaneously with the rapid-fire parade of announcements (ChatGPT passes the bar exam! Bing’s chatbot can browse the web! Buzzfeed replaces journalists with AI! AI tools coming to Gmail and Google Docs!), come the parade of warnings about how AI will flood our communications, take our jobs, enable hackers, empower dictators, and – why think small? – end life as we know it.

Given the pace of AI development, the scale of its impact, and the breadth of potential risks, a tendency to panic is understandable. It’s hard to even know where to start, and there’s no consensus as to how we should proceed. For example, the recent call for a six-month pause in AI development, from the portentously named Future of Life Institute, has been variously criticized as insufficient, excessive, too hasty, too tardy, overly dramatic, or understating the problem. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed.

We’ve Been Overwhelmed Before; We Got Over It

We’ve faced overwhelming problems before. Consider climate change, which began to be recognized as a potentially serious problem as far back as the 1950s.

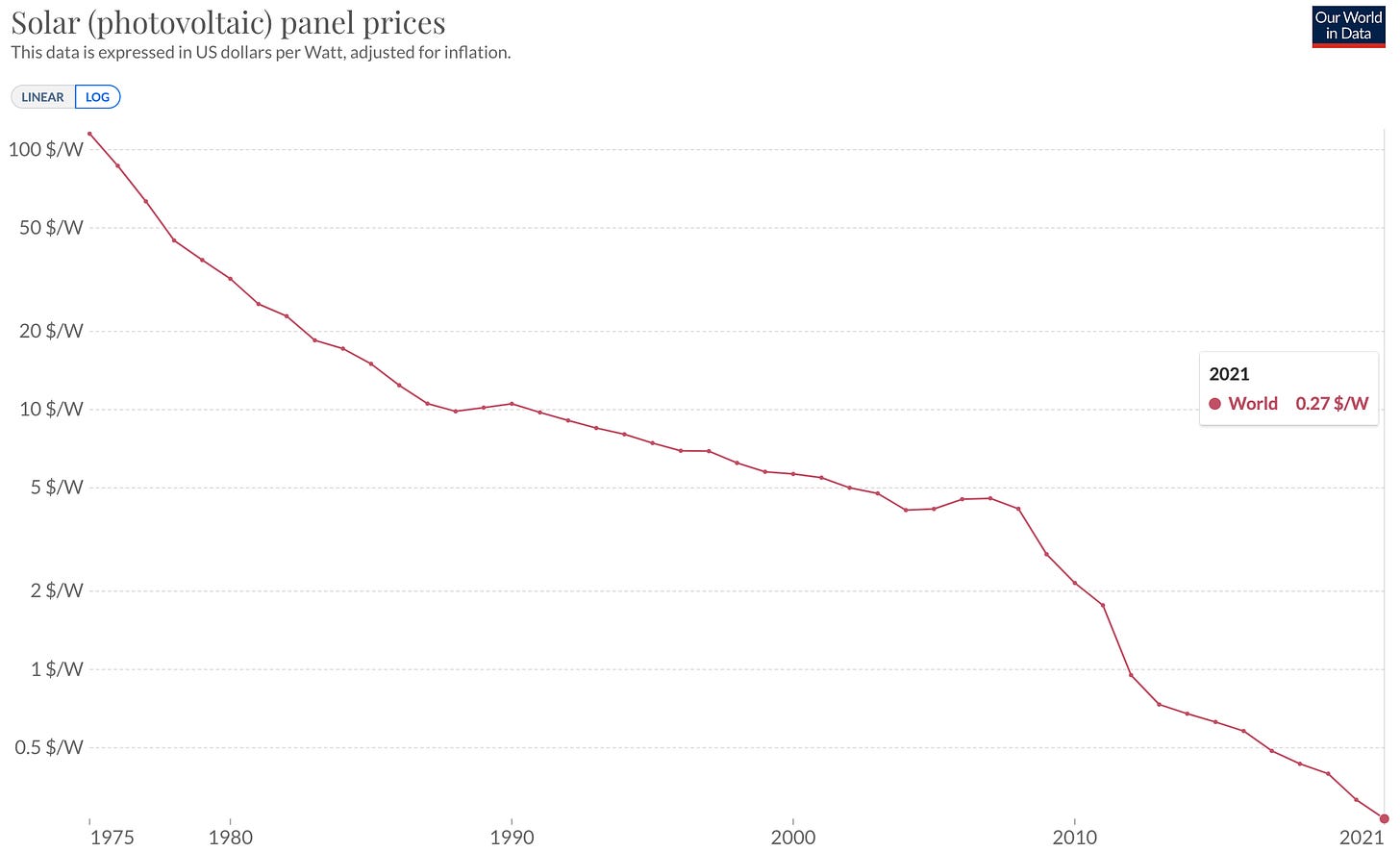

At the time, it was hard to picture a way out. Few of the solutions we’re now relying on to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions were available or practical. The price of solar panels in 1975 was approximately 400 times higher than today. Wind turbines, batteries, electric motors, and other key technologies were relatively primitive as well, and it wasn’t obvious that they could be made economical. The conversation around nuclear power was soon to be dominated by Three Mile Island and Chernobyl. Oil companies, automotive manufacturers, and other vested interests were firm in their opposition to any significant action, the political will to protect the climate was lacking, and opposing voices were under-resourced and hampered by the lack of a compelling vision for controlling emissions without sacrificing prosperity.

For decades now, it has been easy to feel overwhelmed by the prospect of climate change. The problem was vast, the impact profound, the solutions unclear, the opposition powerful. To halt warming would require wholesale changes to power generation, transportation, heating, industrial processes, and even, for crying out loud, the digestive processes of cows. All multiplied by every country on Earth.

Despite the obstacles, some people kept at it. Scientists studied the problem, visionaries and entrepreneurs pioneered new technologies, activists and advocates prompted government action. Countless individuals have switched to climate-related careers, put solar panels on their roof, or otherwise found ways to take action. The first World Climate Conference took place in 1979. The Kyoto Protocol was passed in 1997; the Paris Agreement, in 2015. The United Nations Climate Change Conference has now met 27 times. And somehow, step by step by step by step by step, we have made astounding progress, to the point where solar power is cheaper than coal, major car manufacturers have announced an end to internal combustion engines, and we are approaching the point where demand for fossil fuels will finally enter a permanent decline.

This required dedication, creativity, bravery, passion, intelligence, and hope. It’s been fucking hard work and it’s still not finished. It’s taking longer than we’d like, with too much harm done along the way. But in the battle against climate change, the tide is finally turning1.

Parallels Between AI Risk and Climate Change

Is AI risk sufficiently similar to climate change to allow us to draw lessons from the latter? I think so.

In both cases, there are a wide range of potential effects, mediated through a single channel. For climate change: heat waves, drought, sea level rise, and many other ills are all driven by the level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. For AI: targeted misinformation, job loss, and the potential for a Terminator scenario are all driven by increased AI capabilities. And for each, there is a steady drumbeat of present-day incidents – wildfires, viral deepfakes – drawing attention to the topic.

There are many sources of greenhouse gas emissions, ranging from transportation to rice farming, deforestation to cement production. There are also multiple sources of increased AI capability: larger budgets, improved training techniques, better neural net architectures, customized silicon.

The solutions which were apparent initially (climate: drastically reduce energy usage; AI: halt development of advanced models) were highly burdensome. Innovations (improved solar panels; AI alignment techniques) may reduce the burden, but will take sustained effort to develop.

In both cases, many parties are contributing to the problem, and government action – all the way up to the level of international agreements – will be needed to get everyone to stop. The solutions will be complex, and we will need to build “administrative capacity” – regulatory agencies with a large, skilled staff – to carry them out.

For climate change, elegant policies such as carbon pricing have proven difficult to enact. Some regions have “cap-and-trade” systems which are meant to provide a carbon price, but they often have so many loopholes as to be of little benefit. Instead, progress has been made through an ugly mishmash of efficiency standards, subsidies, research grants, rebates, promotional campaigns, and other ad-hoc measures. For AI safety, we may have to rely on a similar patchwork of politically expedient measures.

Climate polluters often ignore options that would reduce their emissions, such as improved insulation, even if those choices would save them money. This occurs due to lack of knowledge, risk aversion, and other “friction” effects. As a result, economic incentives (whether stemming from artificial subsidies or intrinsic technological superiority) are often not sufficient, and must be backed up by mandates. The same may prove true with regard to AI safety.

There is no clear level of action that can be designated “good enough”. Climate change is a continuous phenomenon; each tenth of a degree of warming produces incrementally worse effects2, and there is no particular temperature threshold such that any degree of warming below that threshold is fine and anything beyond it is disastrous. Targets like 1.5°C or 2.0°C are rallying cries, not fundamental properties of the Earth’s climate system. For most AI risks, the same holds: each incremental increase in AI capability may increase the amount of spam, job loss, and automated crime, but there is unlikely to be a specific threshold at which things suddenly tip from rosy to apocalyptic. Of course there is one big exception: the threshold at which AI could break loose from human control. However, we don’t know where that threshold lies, and so we can’t use it to set a specific safety target. For both climate change and AI risk, any specific goals we set (no warming above 2.0°C, no models above 1 trillion parameters) will be arbitrary.

There are of course some important differences. Some make AI safety more challenging than climate change:

Global warming is objectively measurable, unlike AI capabilities and (especially) risks.

For AI safety, it will be hard to point to positive signs of progress. For climate change, we can celebrate jobs being created, wind farms being installed, and so forth. Success in AI safety work will be more intangible (e.g. incrementally improving our understanding of neural net behavior) and/or negative (another year has gone by without an apocalypse), and thus not attention-grabbing.

Many environmentally clean solutions have reached the point where they can beat out polluting solutions on strictly economic merits. This makes it easier to drag along actors who are not motivated to help mitigate warming. We’re unlikely to reach a point where safe AIs are economically superior to unsafe AIs. (In this regard, restrictions on nuclear proliferation, and to some extent nuclear safety in general, may be a better model than climate change.)

While the pace of future AI progress is hard to predict, things are probably going to move faster than climate change; possibly much faster. Safety work will have to progress faster as well – or else we’ll have to use regulation to slow the pace of AI development.

In the worst case, AI could literally wipe out all human life; a scenario from which we could never recover. There does not appear to be any plausible scenario under which climate change could have that level of impact, especially given recent progress in bending the emissions curve. And it’s possible that we could experience a sudden game-changing leap in AI capability – known as a “sharp left turn” – allowing AIs to take over the world before we’ve recognized that the possibility was even imminent. In climate, major events don’t unfold so quickly, and the likelihood of reaching an irreversible tipping point seems lower.

Others differences should make AI safety easier to address:

Mitigating climate change requires spending many trillions of dollars to rebuild a substantial portion of the entire machinery of civilization (though most of this merely substitutes for money that would otherwise have been spent on fossil fuels and legacy equipment). The dollar cost of AI safety measures will be trivial in comparison3.

For AI, standing in the way of progress is helpful to safety (though of course this is at the sacrifice of beneficial applications). For climate change, this is mostly reversed. Red tape may strangle some coal plants and oil wells, but on balance today it is mostly preventing green projects, and thus interfering with our ability to reduce emissions4.

For much of the history of the climate change movement, few people in the fossil fuel industry acknowledged the climate problem. Many AI practitioners do acknowledge that there are serious safety concerns, and in at least some cases are supportive of efforts to address them. There are even instances of prominent researchers leaving industry to support AI safety efforts, as exemplified by recent headlines such as AI 'godfather' Geoffrey Hinton warns of dangers as he quits Google.

Given these similarities (and differences), what lessons from the fight against climate change can we apply to AI safety?

Play the Long Game

Climate change mitigation has been a decades-long process. Success has required a patient, long-term approach. The same will be true for AI safety.

(At this point, long-timers like Eliezer Yudkowsky would probably roll their eyes and say “I’ve been sounding the alarm for years, and look at how little attention the world has paid. What has patience accomplished?” To this, I would respond that AI has exploded in prominence in recent months, a lot more people are paying attention to safety issues, and intervention is becoming a more accepted idea. I would also note that climate activists probably felt similarly discouraged throughout the 70s, 80s, and 90s.)

Here’s what playing a long game means:

We shouldn’t expect to solve the problem overnight.

In fact, we shouldn’t ever expect to “solve” the problem, just as we haven’t “solved” the problems of war or crime. The best we can hope is to manage the problem, through unending vigilance.

We still have time to prepare. The kinds of disruption that AI will cause in the next few years are not so very different from challenges we’ve faced in the past, and that society already knows how to respond to, more or less. The really serious risks come in the middle and long run.

As a result, our focus today should not be on solving AI risks, it should be on creating the conditions under which AI risks can be managed successfully.

How can we “create the conditions under which AI risks can be managed successfully”? To begin with, we should review successful movements from the past. Not just climate change mitigation, but also protecting the ozone layer, limiting the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons5, and others. What lessons can we draw from these movements? How did they gather resources, build support, shift norms, and generally accomplish their goals? I’ll spend the rest of this post exploring some of the key ideas.

Take a Big-Tent Approach

Various branches of the climate change movement may disagree on some aspects of the solution, such as the role of nuclear power in a clean grid. But there is widespread recognition that it is all one big problem, triggered by the common mechanism of global warming. You don’t see organizations formed specifically to fight sea-level rise, or heat waves, or shifts in rainfall patterns. Everyone recognizes that, regardless of which specific symptoms are most relevant to your personal location, there is a common enemy: greenhouse gas emissions.

AI safety will benefit from a similar big-tent approach. As I said last time:

Addressing AI risks will almost certainly regard collective action; for instance, to discourage reckless deployments of advanced AIs. A holistic approach will make it easier to lay the political and social foundations for such actions.

By framing AI risk broadly, we can avoid infighting, and present a simpler message to the public.

Some of the techniques (such as better approaches to alignment) that we’ll develop to address near-term risks, will also help mitigate catastrophic risks.

Slowing the pace of AI will be helpful across the board – if done as part of a larger program of safety work.

Develop Effective Messaging

Avoiding negative impacts from AI is a grand challenge, and at the end of the day, success at any grand challenge hinges on getting people on board6. The climate picture would look much bleaker if not for the millions of people who vote for environmentally friendly candidates, install heat pumps, donate to green organizations, and find careers in climate. Building that support requires good messaging: we need to talk about the problem in a way that people will understand it, support efforts to solve it, and feel motivated and empowered to participate.

This is hard.

For an example of how not to go about effective communication, see Eliezer Yudkowsky’s recent editorial in Time magazine. Near the end, he says (emphasis added):

Make it explicit in international diplomacy that preventing AI extinction scenarios is considered a priority above preventing a full nuclear exchange, and that allied nuclear countries are willing to run some risk of nuclear exchange if that’s what it takes to reduce the risk of large AI training runs.

To be clear, he is saying that we should take military action (if necessary) to prevent other countries from training advanced AIs, even if that risks nuclear war. His logic is as follows:

Nuclear war is very bad, but not as bad as all of humanity being wiped out by AI.

(Yudkowsky believes that) development of advanced AIs inevitably leads to the end of humanity, while threatening to bomb a data center – or even actually doing it – merely risks war, which only might escalate to nuclear war.

The risk of killing many people is preferable to the certainty of killing everyone.

I grant the logic here. I even agree that his premises are at least plausible, though I suspect that an insistence on an immediate “moratorium on new large training runs” may be unnecessarily strident. But even if he’s correct in every detail, this is lousy communication. He never bothers to walk through the logic that an AI apocalypse would be worse than nuclear war. He barely acknowledges what a massive step this peremptory military-backed ban on large training runs would be. He doesn’t bother to explore alternative solutions, even if only to dismiss them. He doesn’t acknowledge the international coalition-building that would be necessary for such an approach to have the slightest hope of success, beyond the four offhand words “make immediate multinational agreements”. This is not how you get the average Time reader on board with your ideas.

If we’re going to succeed, we’re going to need to get policymakers, practitioners, and the general public on board. That’s not an annoying distraction from the “real work” of developing techniques for AI safety, it is the real work. We’re not going to get there by expecting the average reader to speed-run, in a single page, a chain of logic that the AI risk community has been discussing for years. We’re not going to get there with jargon about “paperclip maximizers” and “instrumental convergence”. We’ll need clear, thoughtful, simple explanations of the key ideas, repeated patiently and consistently, over and over and over again.

Stay Positive

With regard to both climate change and AI safety, it’s easy to fall into pessimism. Easy, but not helpful.

A “doomer” attitude promotes depression and inactivity. Doomer messaging pushes people away. If we want to tackle the problem, and especially if we want to bring more people on board, we need to present a hopeful outlook, and provide people with options for constructive action. As Matthew Yglesias said in People need to hear the good news about climate change:

…when I see story after story after story on climate anxiety, I am mostly not reading stories of people who decide they want to increase their level of commitment to addressing climate change and then take action to do so. Everyone might feel better and the planet would be much better off if the anxious weren’t paralyzed by depression.

Positive messaging has a couple of aspects:

We should describe the problem as solvable. This doesn’t mean minimizing it, pretending that there’s no risk, or that we’re guaranteed to find solutions. It simply means framing it as “a problem we can work at” rather than “a doom we are helpless to prevent”.

We need to present constructive actions that can be carried out today. These don’t need to be end solutions, merely steps along the way. If people see a path forward, they will be more likely to support positive action. If people see steps they can realistically take themselves, they build a habit of positive action.

Note that it’s easier to convey a positive message when you have some positive facts to point to. In climate change, early successes generated momentum that have helped contribute to the current situation, where radical changes start to seem not only possible, but inevitable. For AI safety, it will be helpful to find some early wins, even if they are not hugely consequential. (One viewpoint holds that drawing attention to small wins removes the pressure for larger change. But I don’t think the history of climate change mitigation, or other successful movements for that matter, bears this out.)

Technical Achievements Unlock Policy Achievements

Governments around the world have enacted policies mandating a shift to green technologies, from renewable energy to heat pumps to electric cars. With 1970s technology, this would have been unimaginable: the public would not have accepted the price / performance of the clean technologies of the time. New technologies can shift the cost / benefit curve of climate safety, or AI safety, and thus reduce the barrier to political solutions.

This can start with small things. For instance, if there were a robust way of watermarking generated content, we could mandate that it be put into use, thus achieving an early victory for regulation. Without that technical solution, we can’t get the policy win.

Build Organizational And Political Capital

Positive steps toward mitigating climate change don’t come out of nowhere. Consider the Inflation Reduction Act, recently enacted in the United States. There are at least two noteworthy things about the greenhouse gas reduction provisions in this bill:

They’re enormous in scale. The precise amount of money that the federal government will wind up spending as a result of this bill depends on future events7, but estimates range from hundreds of billions up to a trillion dollars or more.

While the bill unavoidably emerges from the legislative sausage factory, many of the provisions are in fact very well designed.

The bill’s vast scope was made possible by decades spent raising the prominence of the climate issue, to the point where the public was ready for large-scale action and Congress and the White House were interested in delivering. Meanwhile, many of the well-crafted details in the specific language of the bill come from organizations who have invested years in developing effective climate policies, while also building trusted relationships with politicians, staffers, press, donors, and politically connected groups.

To act effectively on AI risk, we will similarly need to build organizations that can, in addition to doing the policy work, nurture the broad array of relationships necessary to distribute and support that work. We can start building those organizations and relationships today; we don’t need to finalize any sort of AI safety agenda first. Many of the specific policies in the IRA were worked out relatively recently, but the organizations which helped that happen have often been around for much longer. Just as you can begin training for a race before you know the precise route, we should begin today to develop the organizational and political capital that will be needed to address AI risk. (If you know of organizations that are doing this kind of policy and political work, please let me know! You can respond in the comments, or drop me a line at amistrongeryet@substack.com.)

As Zvi Mowshowitz said, with regard to the call for a six-month pause on training large models:

The pause enables us to get our act together.

It does this by laying the groundwork of cooperation and coordination. You show that such cooperation is possible and practical. That coordination is hard, but we are up to the task, and can at least make a good attempt. The biggest barrier to coordination is often having no faith in others that might coordinate with you.

I essentially agree with Jess Riedel here. If you want coordination later, start with coordination now … even if it’s in some sense ‘too early.’ When it isn’t too early, it is already too late.

Patiently Shift Overton Windows

For any given topic, the “Overton window” is the range of ideas generally considered plausible or acceptable in public discourse.

To put ourselves on a course to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions, we’ve had to shift a lot of Overton windows. I wrote about this a while back in the context of climate change: To Be Possible, An Idea Must Seem Inevitable. Imagine telling a 1970s climate activist that GM had announced that they would categorically exit the internal combustion business. It would have seemed impossible to them, because in the 1970s, an end to internal combustion was well outside the Overton window. But by 2021, the idea that internal combustion engines were on the way out had become so mainstream that the CEO of GM actually announced a sunset date.

Similar shifts will be needed to address AI risk. AI researchers are going to have to accept limits on their work, and tech companies will have to accept limits on what models they can build and deploy. Government officials are going to have to understand that it is both possible and necessary to regulate AI. The general public is going to have to internalize the idea that AI poses a wide range of risks, from spam to the end of the world, and that these risks are real but also addressable.

Shifting the Overton window is a gradual process. If you try to move too far, too fast, people reject your ideas as outlandish. This is one of the reasons we need to play a long game. Sometimes a crisis can help; the sudden prominence of ChatGPT has put AI risk on the agenda.

Conclusion

AI risks pose a daunting challenge. We can rise to that challenge by using climate change mitigation as a model. Some important lessons:

This is a long game. Don’t think about how to “solve” AI safety, as something to be completed in the near future. Think about how to establish the conditions under which AI risks can be managed successfully, on a sustainable basis.

To establish those conditions, we’ll need to create organizations that can take thoughtful action, and sustain it over time. Those organizations will need to build long-term relationships with politicians, staffers, press, and other groups.

Take a big-tent approach. If someone is worried about a different AI risk than you, they are your ally, not your competitor.

We’ll need to communicate clearly with the public, developing effective messages that will resonate with a general audience.

Effective messages are positive, expressing hope and pointing toward constructive steps. Doom and despair are uninspiring, and induce people to tune out.

Various parties – AI researchers, tech companies, government officials, the general public – will need to assimilate new ideas, such as the need for regulation of AI. This requires “shifting the Overton window”, i.e. adjusting the range of ideas that society considers to be plausible. Such a shift takes time.

Small victories can help build momentum: they provide grist for positive messages, and normalize the idea that change is possible or even inevitable.

Technical innovation smooths the path for policy achievements, by making the tradeoffs less onerous.

Climate change is coming under control to a degree that would have been hard to imagine until quite recently. This is the result of sustained, methodical action. We should take the same approach to AI risk.

Thanks to Toby Schachman for providing feedback on an earlier draft. If you’d like to join the “beta club” for future posts, please drop me a line at amistrongeryet@substack.com. No expertise required; feedback on whether the material is interesting and understandable is as valuable as technical commentary.

As I wrote last time: not everyone feels that the problem of global climate change is coming under control, but I believe this is what the facts tell us. Progress in key technologies such as solar panels, batteries, and electric motors has been astonishing. Thanks to this, as well as decades of patient work by advocacy and policy groups, we are now seeing carbon-neutral solutions come roaring onto the playing field. The results are not yet showing up dramatically in top-line emissions figures, but that will start to change soon. I’ve written extensively about this in a separate blog; see, for instance, Fossil Fuel Growth Doesn't Mean We're Not Making Progress.

For another data point, this Twitter thread summarizes a recent paper in Nature as stating that existing national commitments to emissions reductions would stabilize warming at 1.7-1.8°C. Existing policies do not match those commitments, but would still be enough to limit warming to 2.1-2.4°C by 2100, and the trend has been for policies to improve over time.

Unless we reach a climate “tipping point”, but the significance of such tipping points is debated, and in any case, no one knows precisely where they might lie.

Ignoring the cost of the opportunities lost by not rushing ahead with unsafe systems.

I blogged about this last year: It's Time To Fight For The Right To Build.

I say “successful” here, even though that success is in most cases far from complete. At least nine countries have nuclear weapons, global warming appears likely to breach 1.5°C, and so forth. My point is simply that for each of the issues I mentioned, the outcome to date has been much better than might have been expected if no effort was made.

And yes, I’m aware that for some of the more extreme AI risks, there is no prize for partial success; “well, at least we delayed the apocalypse by a few years” is not an acceptable outcome. The point remains that if we want to win the future, then in the present we should be thinking in terms of gathering resources and laying foundations.

If there are any smart alecks in the room who want to say “why do we need to get people on board when we could use AIs instead?”, I will reply that if we could be confident in getting good results from that approach, we would already have solved the AI safety problem.

In particular, the IRA grants tax credits for a wide variety of projects, so the cost will depend on the number of such projects which are undertaken during the period of eligibility.

In my opinion the comparison to the climate change activism is kinda iffy in a sense that it should serve as a mostly negative example, being run by unserious people doing it for political power, clout, self-actualization, grift, etc.

Before I show some examples, here's how a serious problem being solved by serious people looks like: at some point for about a week or so a lot of pundits and politicians were calling for a No Fly Zone over Ukraine. Then the serious people noticed, quietly told the unserious people to shut up or else, and the whole thing was promptly forgotten. Any movement inevitably attracts unserious people, but in a healthy movement concerned with a serious problem they are kept on the fringe.

Now consider that Germany has switched from nuclear power to burning coal. And no, burning Russian "green gas" would not have been much better CO2-wise. And no, the conflict in Ukraine had been hot since 2014, serious people would have taken that into account. And if someone tries to excuse that as a result of the complex interplay between idiots in the Green party, anti-nuclear "experts", click-baiting journalists, and misinformed population: yep, the circus is run by the clowns, this is exactly what I'm talking about.

On a related note, consider the propensity of climate change activism to constantly produce medium-term catastrophic predictions, from Al Gore's "Manhattan will be underwater by 2015" to various "we will hit the point of no return in 12 years" claims widely repeated by people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez a couple of years ago.

As you pointed yourself, we are in for a long haul, so the movement _itself_ must be _sustainable_. If every generation of young people is told that the world is burning to a crisp in 15 years, then look around in their thirties and discover that not only nothing much has changed, but also that this sort of catastrophizing has been going since before they were born, that's not _sustainable_.

And again if you admit that this is actually pretty bad but unfortunately we don't have a Climate Activism Czar that could tell Al Gore, questionable experts, and click-baiting journalists to shut up: yes, the circus is run by the clowns. You really want it to be otherwise, but that's how it is.

Or consider this: Joe Biden ran for president on a platform of strangling the US oil industry, killed the Keystone XL pipeline on the first day in the office, appointed a very anti-oil head of DOE, all that, to the cheering of journalists and voters. Then the gas price in the US doubled. Note that it was not merely predictable, but essential to the plan. You limit the supply of gas, the price rises until the demand also reduces to meet the supply because people can't afford gas, so they have to drive less and less CO2 is emitted.

In a world where all those climate activists including the President and all his advisors and experts and journalists and Democrat voters were serious (albeit not very bright) people, we would have had a shocked revelation: it turns out that gas is produced by the oil industry! Then, while fighting climate change is important, but not at this cost. Or maybe the other way around, we should tighten our belts for the greater good. Instead Biden released part of strategic oil reserves and gave out a bunch of drilling permits, while experts explained that the price surge was caused by the Covid rebound and the war in Ukraine and was not Biden's fault.

Which, look, I'm not an expert, but first of all, _not for the lack of trying_. But even more importantly, those expert explanations had the completely wrong tone! An expert serious about fighting climate change would say that unfortunately Biden's policies had a negligible contribution to the gas price surge, so if the administration wants the price to stay high after the effects of covid/war are over they must double down on strangling the oil industry. An expert who tells me not to worry, the price will go back down, is very unserious.

And to emphasize, it's not just a few journalists getting overly enthusiastic about a stupid idea, it's the whole Curtis Yarvin's Cathedral, the entire office of the POTUS plus journalists, experts, voters.

Or consider this: who thought that making an underage autistic girl from a multimillionaire family with visible symptoms of FAS the literal face of the movement was a good idea? So that some Yellow Vest truck driver upset about his livelihood being destroyed would read an article about Greta crossing the Atlantic on an electric yacht to speak before the UN, look at her face, and realize that while he might have problems this kid knows better what's good for everyone and has a better moral compass, really he should be ashamed for driving his stinky truck instead of an ecological yacht?

That's not to imply any offense to Greta Thunberg, none of that is her fault, but there's this vaguely defined swarm of people who made her the face of the movement and wrote gushing articles about her yacht, and yes that's a problem that they do this for reasons that have nothing to do with fighting the climate change and that there's nobody who could tell them to shut up.

So, why exactly is supporting a movement run by unserious people is bad? First of all, it's a waste of resources. Second, when the unserious people wield actual power, it causes real harm, like with Germany switching to coal or the gas price surge. Third, it causes unsustainable reputational damage. Finally, while the "unserious people" are unserious about the stated goal of the movement, they are very serious about obtaining and holding onto power, so you're empowering them to keep the actual serious people away from power. Observe that Elon Musk is now contending the number 1 most hated person by progressives spot, for no clear reason.

Yes, there were some impressive things achieved in the fight against global warming, but from what I can tell all of them were the result of some nameless bureaucrat signing off on a subsidy for solar panels or whatnot, then the free market doing its thing while the government keeps out. With no pomp, no demonstrations in support or politicians taking credit. While pretty much everything that involved _visible politics_ was harmful to the movement and its stated goal.

So that makes me pessimistic about your ideas about AI control that all involve _politicking_ in some form and none involve the government just throwing money at some private businesses, no strings attached. Ironically, the only thing I see that might save it somewhat is that maybe the underlying reason the climate activism had been entirely captured by unreasonable people is that climate change (unlike, say, the war in Ukraine) is not a serious problem. If the advancements in AI prove to be a serious problem, maybe we will have serious people take charge.